Before March of 1945, Hildescheim had 68,000 inhabitants. The town contained established civilian hospitals and the town center held no military installations or anything else of military importance. However, industries outside of the small city did, and many of the townsfolk had worked in these factories. There were factories that produced parts for fuses, ignitions and gearboxes for tanks as well as other important war equipment, one that built parts for torpedoes (even one that was later rumored to have built nose cones for the elusive V-2 rocket). Other plants produced machinery, engine parts, airplane parts, and various weapons. There was also a rubber factory making gas masks, life jackets, rubber boats for both Army and Navy, and rubber parts used for torpedoes and cockpits of aircraft. At this point in the war, however, many industries were not functioning.

Although there had been seven or eight minor bomb strikes beginning in July of 1944 hitting a factory, a railroad installation, St. Michaels church and a few buildings in town, nothing was a clue as to the devastation which would utterly destroy the town on March 22, 1945.

In Bomber Command Diaries, it is noted that marking the city center by the “pathfinders” was very accurate. First the city area was “framed” by red and green lights on the ground. The target area was first bombed by a massive shock bomb that destroyed the roofs and windows of the buildings. Bombs from the first wave fell concentrated in the city center. Corner houses were the most beneficial hits, because the rubble quickly choked the roads, preventing access by emergency vehicles as well as escape routes for citizens. The incendiaries followed, and in minutes turned medieval towns into towering infernos. By this point in the war, this procedure was well rehearsed.

Following the guide for efficiently burning medieval city centers, they flew very low over Hildesheim, bombing the medieval city center until everything caught fire. The huge fires and heavy smoke then predictably prevented people from escaping. 438.8 tons of mines and high-explosive bombs plus 624 tons of incendiary bombs were dropped, and the high-explosive bombs, as intended, tore open the houses so the deadly 300,000 incendiary bombs could kindle a fire tower.

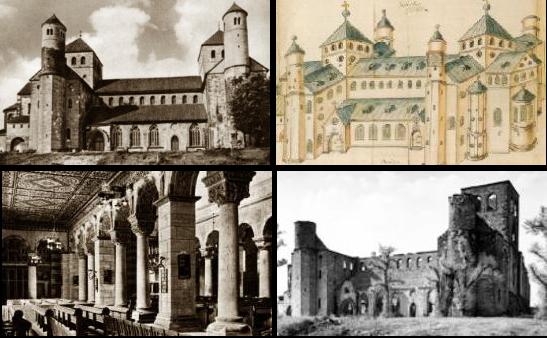

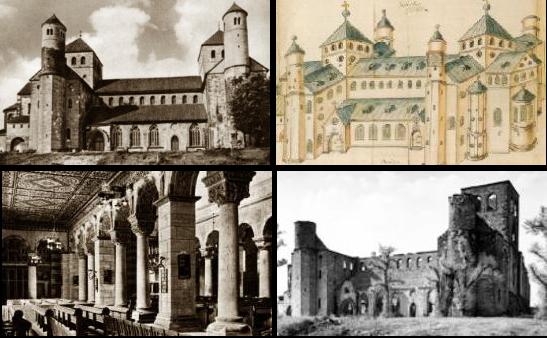

The city center, which had retained its medieval character until then with 1,000 half-timbered houses, ceased to exist. The Romanesque St. Mary’s Cathedral, below right, dated from the 9th century.

The death toll was not as great as in many other bombed cities, but at least 1,645 civilians were killed, among them 204 women and 181 children, 68 of which were under the age of six, 79 under fourteen and 34 of unknown age. 277 victims’ ages could not be ascertained. Many of the other victims were elderly. 50 orphans were created. The sad irony is that, while the obliterated town center held no military installations, Hildesheim’s several vital factories in prime war industries and also the major plants of importance and subsidiary factories on the outskirts of the town were virtually untouched by the bombing, even the large central goods station with connections to all of the German Reich! The VDM Works was the only clearly established factory which was precisely bombed, but it was previously bombed on March 14, 1945 by 60 US bombers, and it was still not completely destroyed during this attack, only the Senking factory was.

22 March 1945: 227 Lancaster bombers, 8 Mosquito’s of 1 & 8 Groups. 4 Lancaster bombers lost. The target was the railway yards; these were bombed but the surrounding built up areas also suffered severely in what was virtually an area attack. This was the only major Bomber Command raid of the war on Hildesheim and the post-war British survey found that 263 acres, 70% of the town, had been destroyed. The local report states that the inner town suffered the most damage. The Cathedral, most of the churches and many historic buildings were destroyed. A total of 3,302 blocks of flats containing more than 10,000 apartments were destroyed or seriously damaged. 1,645 people were killed.

Hildesheim is 20 miles SE of Hannover and is a railway junction of some importance. The town centre is largely built of half timbered houses and has preserved its mediaeval character. There are various industries, mostly in the hands of small undertakings. In addition to the works mentioned the town’s activities include the manufacture of agricultural machinery and a sugar refinery. Lancasters and Mosquito’s attacked the town. The Master Bomber assessed the markers as being 200 yards off the aiming point, and therefore a good concentration of accurately placed markers was maintained. Bombs were seen to fall in the marshalling yards to the north west of the aiming point and the (?) centre of the built up area was soon a mass of smoke. Smoke rising to 15,000 feet could be seen for approximately 200 miles on the return journey. The intention was to destroy the built up area and associated industries and railway facilities. Almost the entire town was devastated, only the extreme suburban areas having escaped destruction. (End)

In 1701, musician Georg Philipp Telemann did his preparatory studies at the Gymnasium Andreanum at Hildesheim, a school first mentioned in the year 1225. The school buildings of the Andreanum were destroyed as was the state theater. Hildesheim, like many bombed cities, was poorly rebuilt in concrete after the war. However, in the late 1970s, reconstruction of the historic center began with replicas of the original buildings using their old plans. Today, it looks un-bombed, in that “theme park” sort of way. It is not easy to find pictures of Allied bomb damage. Cameras were confiscated from German civilians during occupation, and such photos were kept top secret for many years, only to come top life with the internet. It is especially difficult to find images of German cities that fell under communist occupation for decades.

When the Hildesheim Cathedral suffered near total destruction, a legendary 1,000 year-old rosebush next to it was also burned and buried beneath the rubble in 1945; its roots remained unharmed and soon the bush was thriving once again.